Briefly, peri-implant diseases are to implants what periodontal diseases are to teeth. Both diseases initially affect the marginal mucosal tissue (keratinized or nonkeratinized), and both diseases can invade and destroy the osseous support of the tooth or implant, which can lead to their loss.

The prevalence of peri-implantitis, according to a recent review by Heitz-Mayfield and Mombelli,(1) is 10% of implants and 20% of patients 5 to 10 years after implant placement. Much higher and discrepant values have been reported by other authors, which is due, among other reasons, to the many variables that affect the published results, starting with the fact that there is still no definition of peri-implantitis that is universally accepted by the scientific community. There is no consensus regarding the probing depth values or loss of bone support due to peri-implant inflammation that define the presence of peri-implantitis.

In addition, individual factors (lack of oral hygiene, poorly controlled diabetes, smoking, periodontitis––including treated periodontitis) and others specific to the implant site, its physical characteristics, the operator and surgery significantly influence the outcome of treatment with osseointegrated implants, including short- and long-term complications.

Briefly, peri-implant diseases are to implants what periodontal diseases are to teeth. Both diseases initially affect the marginal mucosal tissue (keratinized or nonkeratinized), and both diseases can invade and destroy the osseous support of the tooth or implant, which can lead to their loss.

The prevalence of peri-implantitis, according to a recent review by Heitz-Mayfield and Mombelli,(1) is 10% of implants and 20% of patients 5 to 10 years after implant placement. Much higher and discrepant values have been reported by other authors, which is due, among other reasons, to the many variables that affect the published results, starting with the fact that there is still no definition of peri-implantitis that is universally accepted by the scientific community. There is no consensus regarding the probing depth values or loss of bone support due to peri-implant inflammation that define the presence of peri-implantitis.

In addition, individual factors (lack of oral hygiene, poorly controlled diabetes, smoking, periodontitis––including treated periodontitis) and others specific to the implant site, its physical characteristics, the operator and surgery significantly influence the outcome of treatment with osseointegrated implants, including short- and long-term complications.

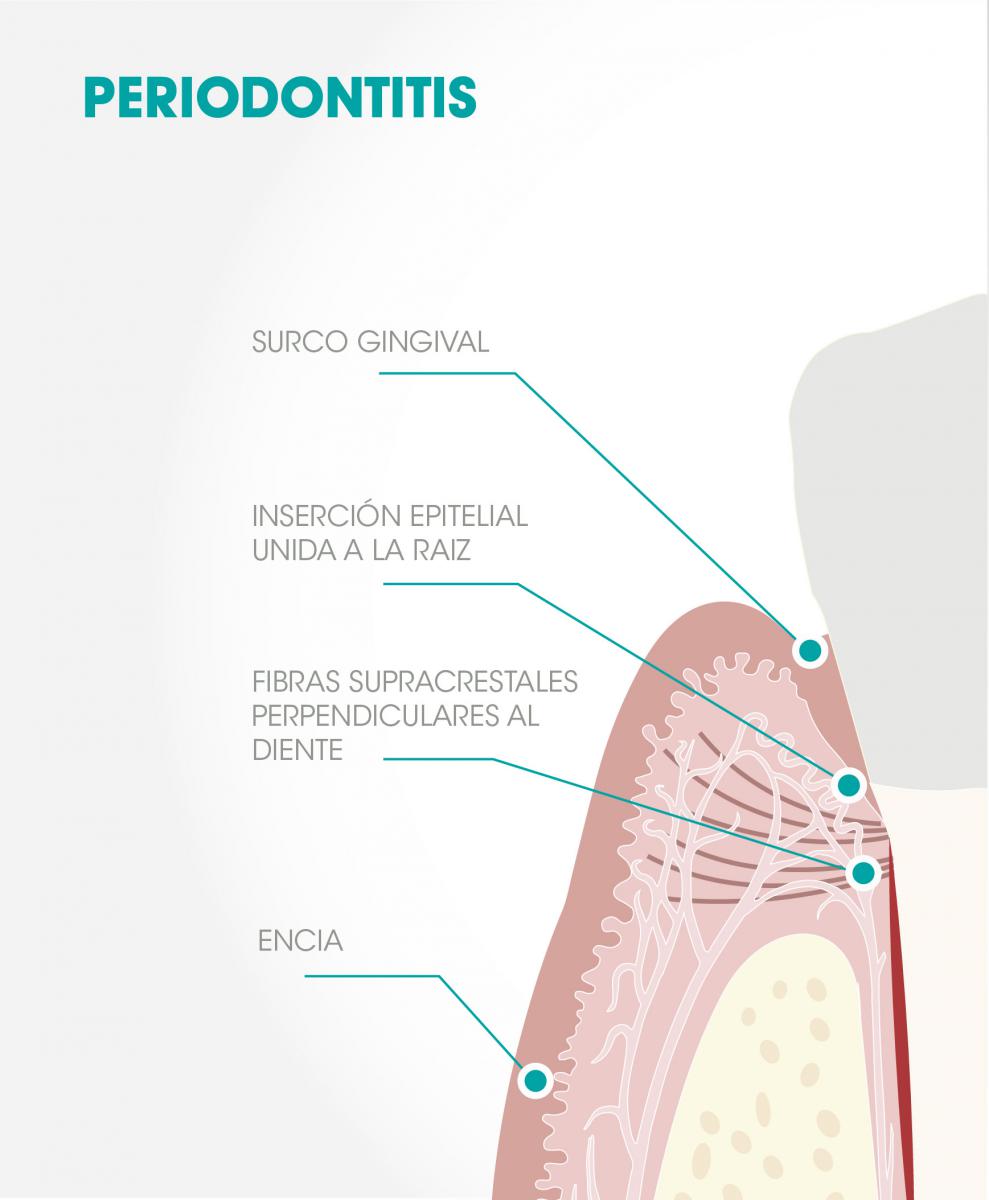

Fig 1. Periodontitis: Following surgery, the gingiva attaches to the root of the tooth by means of an epithelial attachment that separates it from the bone by the fibers of the alveolar crest barrier that attach the gum to the tooth perpendicularly.

Most of the results reported in the scientific literature have serious methodological limitations, some of them very difficult to avoid.(1) Consequently, it is not surprising that the authors of systematic reviews of the treatment of peri-implantitis conclude by noting the impossibility of determining the best therapeutic protocol because all of them are deficient.(2)

In this regard, it is interesting to consider, as Heitz-Mayfield and Lang(3) have noted, that while the treatment of periodontitis shows excellent results after many years, the surgical treatment of peri-implantitis “does not guarantee long-term stability without reinfection, so their results should be considered unpredictable.”(3) This occurs even though the parallelism between the two entities is very evident and the therapeutic protocols are similar in both cases. In contrast, there are reasons that might justify these differences, such as: a) the absence, in the case of implants, of the protective network of alveolar crest fibers connecting the gum to the tooth and that separate the protective periodontium (gums) from the supportive periodontium (cement, alveolar bone, periodontal ligament) Fig 1,(4) b) the absence of alveolar crest fibers, Fig 2, c) the rough helicoidal surface of the implant (in this sense, can the biofilm be adequately eliminated, even when working on the open tissue? Can an epithelial bond be expected to form over this surface, the traditional form of sealing a treated periodontium?)

![]()

Fig 2. Peri-implantitis: After surgical treatment, the gingiva contacts the implant (but only binds to it with difficulty) by “insertion” epithelium that reaches the bone. There are no alveolar crest fibers, but instead bundles of fibers parallel the implant with no barrier function.

In view of the above, it is reasonable to think that the peri-implant “wall” and the implant itself have certain structural deficits that make their response to bacterial aggression less effective and more imprecise than observed in the case of natural teeth. This causes the rate of bone loss in cases of peri-implantitis to be faster than the rate of bone loss in cases of periodontitis.(5)

On the other hand, once peri-implantitis is established, both mechanical removal and different protocols for chemical or other types of removal of bacterial biofilm from the implant surface do not seem to be able to achieve satisfactory results in the mid- and long term, nor can they do so predictably.

Consequently, the best treatment of peri-implantitis is when treatment is not needed, i.e., to prevent the occurrence of mucositis, which is the step that precedes peri-implantitis. That means to control risk factors, when possible, and to evaluate, assess and, if necessary, modify local factors that may influence the evolution of the case before implant placement (e.g., arch position, the characteristics of the marginal soft tissue and bone bed, prosthetic considerations, etc.).

The presence of mucositis requires treatment to prevent the progression to peri-implantitis. Since mucositis is an infection, the patient’s oral hygiene must be optimized, and then the supra- and subgingival bacterial film should be eliminated (reduced?) mechanically and local antimicrobials used, ideally in the form of mouthwashes or introduced into the peri-implant sulcus. The few existing controlled clinical studies on this topic have shown that this protocol is generally capable of resolving the mucositis in most cases.(3)

In the case of peri-implantitis, as indicated, there is no evidence that any therapeutic protocol is clearly superior to any other (except surgery over non-surgery). Most authors propose debridement of the contaminated surfaces using different methods and materials, with or without the addition of antibiotics (local or systemic), followed by chlorhexidine rinses for several weeks. At times, depending on the anatomy of the peri-implant bone defects, different filler biomaterials can be used for the purpose of regenerating bone and increasing the support of the implant (which does not mean re-osseointegration). However, the results are unpredictable and can be disappointing in many cases, especially in the absence of an adequate maintenance phase after successful treatment.

In conclusion, the treatment of peri-implantitis is far from solved. It is not simply a matter of properly eliminating the biofilm directly responsible for its appearance, but of beginning to seriously consider the critical role of peri-implant reinfection. At present, implant design is what ensures their longevity because it makes osseointegration possible, but the same design can mean implant failure if the infection reaches and destroys the bone. Research in implantology should try to bring the peri-implant scenario as close as possible to the periodontal scenario, so that the implant surface is biologically acceptable to the surrounding tissues after treating the disease, something that has been perfectly feasible for years in periodontics, but not yet in implantology.

References

1. Heitz-Mayfield L, Mombelli A. The Therapy of Periimplantitis: A Systematic Review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2014; 29 (Suppl) 325-345

2. Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Worthington HV. Treatment of peri-implantitis: what interventions are effective? A Cochrane systematic review. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2012; 5 Suppl: S21-41

3. Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Lang NP. Comparative biology of chronic and aggressive periodontitis vs. peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000. 2010 Jun;53:167-181.

4. Saglie R, Johansen JR, Flotra L. The zone of completely and partially destructed periodontal fibres in pathological pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1975;2(4):198-202.

5. Lindhe J, Berglundh T, Ericsson I, Liljenberg B, Marinello C. Experimental breakdown of peri-implant and periodontal tissues. A study in the beagle dog. Clin Oral Implants Res 1992: 3: 9–16.